"I want to help others understand that opioid addiction is a medical condition, one that can be prevented and one for which recovery is possible."

I was raised in Delaware County, where I continue to live and where I have very strong family and community relationships. I’m semi-retired, and when I’m not doing advocacy work, I spend the majority of my time with my four adult children, seven grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

I’ve been surrounded by addiction my entire adult life, but no one had ever died. There was much chaos and heartache, for sure, but never death. Loved ones eventually went to rehab, moved into recovery, and life went on. That all changed three and a half years ago when my 22-year-old grandson Eric died of an accidental heroin overdose. Because of my past experiences, I thought I understood addiction, but when we lost Eric, I realized that I had no real concept of the scope of the problem surrounding opioid addiction.

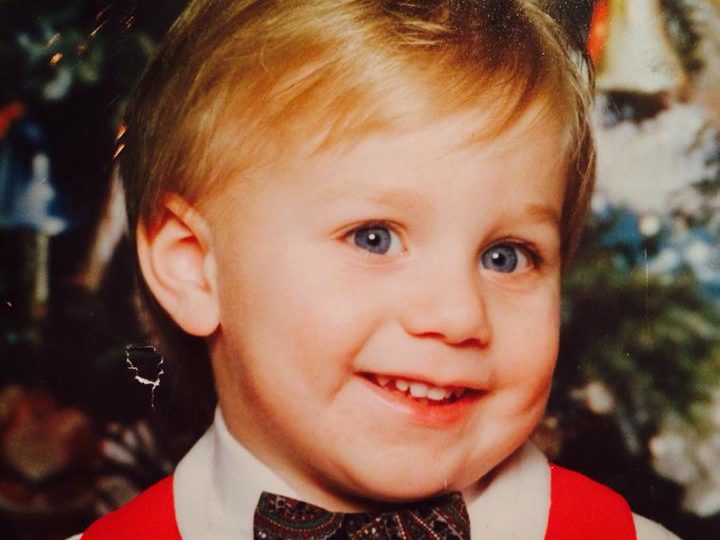

Eric was my first grandchild and we had a very close relationship his entire life. Our bond was incredibly strong. He was a great kid with big blue eyes, a beautiful smile, and a laugh that was absolutely infectious. He had a heart of gold and was a friend to everyone he met. He especially looked out for his mother and younger sister. We began noticing changes in Eric around the time he started high school. His grades were slipping; he was losing weight; he was prone to mood swings. We believed he was experimenting with alcohol and perhaps marijuana but figured he’d work through it because he had a good moral compass. He graduated high school and went onto community college.

We continued to feel that something was wrong; he just didn’t seem like the Eric we knew. We suspected drug use was involved and addressed it with him many times, but he would always say he was fine. And then one day I got a call from my daughter that Eric was in the hospital. They had found him unconscious on the bathroom floor at home. He had overdosed on prescription pills that had not been prescribed to him. They got the drugs out of his system and sent him home. We now knew that Eric did have a drug problem, and we were worried. We talked with him about it and tried to get him to go to rehab, but he said he didn’t need it, that he could stop on his own. He quit community college not long after that overdose, saying he needed to figure out what he wanted to do with his life before going back. He was working but seemed to lack a real focus.

In February 2014, Eric was in a car with friends and they were pulled over by the police. They had heroin, and Eric was arrested. We knew Eric had been using drugs because of the earlier overdose, but we had never suspected that heroin was involved. To say we were shocked doesn’t begin to describe our emotions. Eric finally talked openly with us while his legal issues were being processed. He had started with alcohol and marijuana in high school. Somewhere along the way, he was offered prescription pills at a party and he liked the way they made him feel. He continued to experiment with pills but eventually couldn’t afford them, and that’s when he turned to heroin. The person who sold it to him explained it was much cheaper than pills and could be snorted, that he wouldn’t have to use a needle. Eric said he never believed he would become addicted or that he would ever use a needle. He felt addiction was about willpower and that he was stronger than the drug. But very quickly, he realized he was addicted and he had to use a needle, along with more and more quantities of heroin just to feel normal. It wasn’t about getting high at that point—it was about being able to function.

On April 28, 2014, I got a call from my daughter that Eric was in the emergency room. He had overdosed again but had been resuscitated. He had been using heroin with a friend that day, and his friend noticed that Eric had stopped breathing. He administered CPR and got him to the emergency room, where Eric received three doses of naloxone. I went to the hospital to pick him up. They told me he had come within 2 minutes of dying that day. I tried to get him admitted for a psych hold, but wasn’t successful, and he was discharged that night. Despite not getting the psych evaluation, part of me still felt relieved leaving the hospital because I thought being so close to death would discourage Eric from using heroin again. If only I had understood more about addiction that night!

Eric’s court hearing for the February arrest was two days later. I wanted to tell the judge about the overdose, but Eric begged me not to, afraid of receiving a jail sentence. He promised if I didn’t speak up, he’d voluntarily get into a treatment program. I was so happy he was finally willing to get help that I didn’t say anything during the court proceedings. Eric was given a special program and avoided a jail sentence. Eric was true to his word. He did get himself into an outpatient treatment program. It took several weeks after the court hearing to get an assessment at a treatment facility. We had a hard time navigating the system, finding where to go for help and working through insurance issues. We found that accessing treatment for addiction isn’t easy. I still remember how excited he was to finally receive insurance through Obamacare! I was relieved that he was finally going to get the help he needed.

I gave him rides to his outpatient appointments. He was meeting people in recovery and learning how to manage his triggers. He felt the program would work and he would be okay. I remember telling him the program had to work because I couldn’t bury him.

On the last day of his life, just two weeks into the treatment program, Eric called me at 5 p.m. He was frantic, saying someone he cared about needed help. We made a plan to deal with it together. He called back at 8 p.m., saying he was feeling better. I told him we’d meet the next day, that we’d solve this problem, and that I loved him. That was the last time I heard his voice.

He was home alone that night. Sometime after we spoke, he went out and bought a quantity of heroin. He began texting his girlfriend at midnight to come home. When she finally got there, she found him collapsed on his bedroom floor.

Paramedics tried to revive him with CPR and Narcan and transported him to the hospital. My daughter called, hysterical, repeatedly screaming, “He did it again.” As I raced to the hospital, I kept telling myself that he had overdosed twice before and survived, so he would survive this time. But when I got to the hospital and they took us to a quiet secluded room, I knew what was coming. I couldn’t cry at first when they told us he was gone. I knew what they were saying but it wasn’t registering. When they finally led us to the room where Eric was lying on a gurney, and I saw him so still and quiet, the tears did come, along with a sense of overwhelming hopelessness. June 28, 2014.

The day I had been dreading for so long.

After Eric’s death, I went into a deep depression. I had experienced grief and loss in my life throughout the years, but the death of my grandson was not something from which I could bounce back. I began to isolate. It was hard to be around others whose lives were going on as usual. I couldn’t feel joy. I needed to talk about Eric to process my grief, but I felt that talking about him made people uncomfortable. No one knew how to relate to me. I eventually found several grief groups and a wonderful therapist. I also started to educate myself on the disease of addiction, and the more I learned, the more I knew I had to be involved in advocacy efforts to help others understand this issue.

This is why I am sharing my story, so other families won’t go through the devastation my family experienced. I want to help others understand that opioid addiction is a medical condition, one that can be prevented and one for which recovery is possible. Most importantly, I want to be part of the conversation to one day eliminate the stigma. It’s the best way I know to stop the unnecessary deaths.