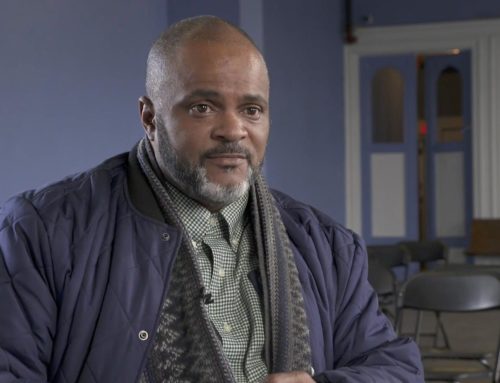

"I’m passionate about helping others improve their lives because so many took the time to help me when I was in a bad place."

I was born in Puerto Rico and immigrated to the States with my family in 1987. I attended school in Philadelphia and spent most of my adolescence and adulthood between the West Kensington and the Fairhill sections of the city. Open air drug markets were common in these areas, and I was exposed at an early age to crime and dysfunction. My brother became addicted to crack cocaine, was arrested, and developed an addiction to heroin while incarcerated. A week after getting out of prison, my mother discovered him unconscious on the living room sofa; he died of an overdose that day. This experience, along with the trauma of watching individuals sell and be arrested for narcotics dissuaded me from ever wanting to experiment with drugs. I did my best at living a normal life and never drank coffee or alcohol and stayed away from marijuana.

In early 2007, I had a motorcycle accident. As a result I sought physical therapy and part of that therapy was pain management. I was put on prescription pain medication, specifically Percocet. I believe the specialist had my best interests in mind, but he never discussed the potential for substance use disorder with me. I was on these medications for about seven months and soon developed a dependency on them. My doctor felt that I was doing better and discontinued the pain medication. I soon began developing flu-like symptoms. I called a friend and told him how I was feeling. He told me that I was going through withdrawal and the symptoms can be treated by taking more Percocet; so I bought more on the streets. I continued taking opioids, not just to help with the physical pain but the emotional pain as well. Eventually the Percocet wasn’t giving me the feeling that I had grown accustomed to receiving. I began taking more and more to keep up with my growing tolerance.

I was taking 50 Percocet a day and the habit was growing too expensive. I was told that I could make the pills feel good again by mixing them with benzodiazepines. I started mixing Xanax, Klonopin, and Valium with the opioids, and that boosted the high. It’s important to note that through all this, I never felt like an addict. The way I saw it, I was taking something that was FDA approved and was at one point prescribed to me. I wasn’t smoking, snorting, or injecting anything. Despite this thinking, I was beginning to get in trouble with the criminal justice system. The first time I went to jail for opioids it was for driving while under the influence. At the time I didn’t think DWI laws applied to medications. I went into county lockup and began experiencing withdrawal symptoms. My body started to convulse, and I began having seizures. I woke up inside the hospital and was told that I had been kept in a medically induced coma for a month because my body kept seizing. A few months later I was sent back to prison for a minor crime I had committed. I got out on probation and felt a strong need to change, but this feeling was gone within six hours of being out.

I eventually began experimenting with heroin, which was always something I had promised myself I would never try. I think people who’ve had substance use disorder progress into their addiction with a list of thing’s they’ll never do. I was checking these things off my list and before I knew it, was back before the same judge who had sentenced me for the DWI and other felony charges. The first time I was before this judge, I didn’t think I’d be back a second time. I really wanted to stop hurting those around me. Despite this intent, I was released back into the same community, with the same people, and started doing the same things; leading to me being before the judge again. I ended up back in jail and began experiencing withdrawals again. I remember looking at myself in the metal plate mirror while in my cell. I was a mess, and told myself that something had to change. If I kept doing what I was doing, I’d either be in and out of prison forever or dead like my brother. I couldn’t stand the thought of continuing to put my mother and girlfriend through this. I got on my knees, threw my hands up, and began asking God to help me change.

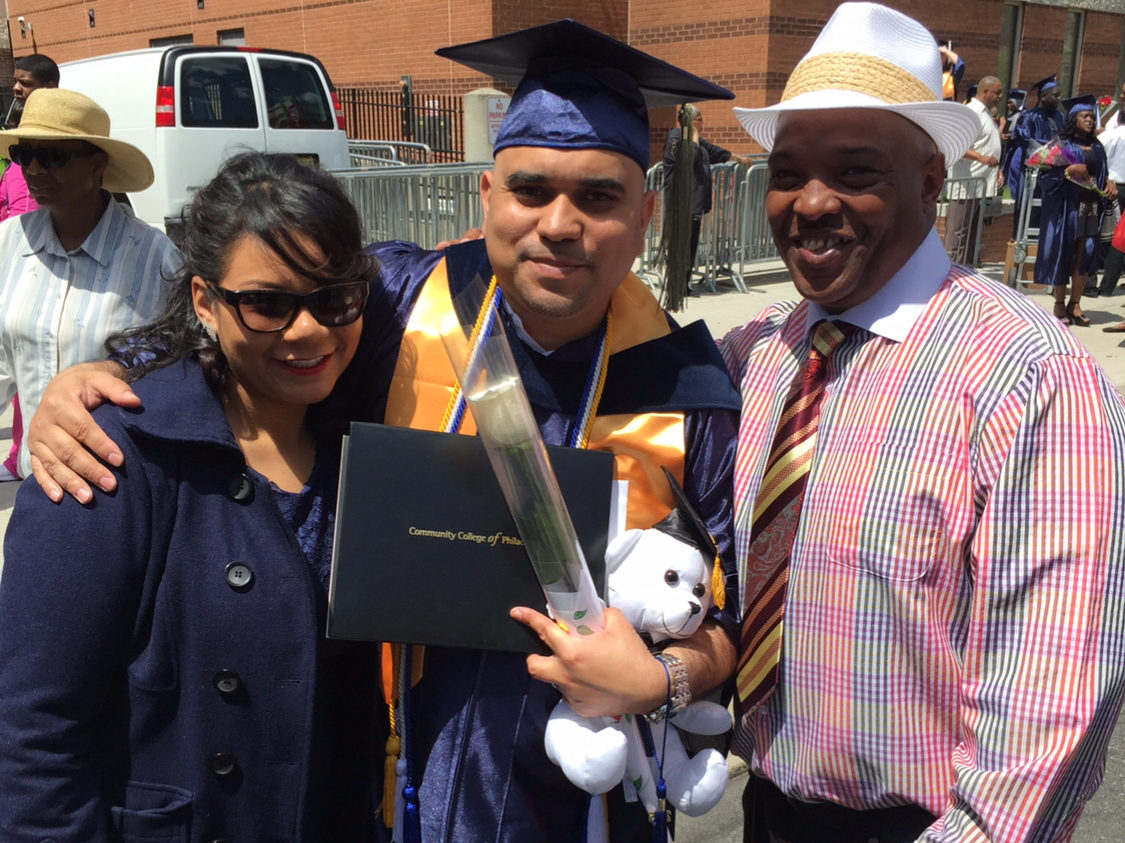

After six months, I was released back into the community. This time I was attached to an in-patient treatment facility for 21 days, was given an intensive case manager, and was required to attend intensive outpatient treatment. I sat down with my father and my girlfriend, who is now my wife, about what should be done next. My wife told me that I needed to take it one step at a time and focus on getting my GED. I stayed in treatment and began attending classes in the evening. I eventually got my GED and felt empowered to change my path through higher education. I’ll always remember the day, not only for obtaining that qualification, but also because I married my girlfriend that day.

I enrolled in the Behavioral Health and Human Service program at Philadelphia Community College and absolutely loved it. My professors seemed to understand the issues of substance use disorder that I was recovering from, which really helped me. I eventually earned my Associate’s degree with the highest honors. I was really proud of myself but was at crossroads for what to do next. I decided to attend Eastern University because their prison outreach programs had a positive impact on me. It meant a lot to me that the school administration and students were willing to come into the prison and interact with us back when I was incarcerated; it made me want to be a part of the school. I was able to earn my Bachelor’s Degree with the highest honors again, but was also at another crossroads. I decided to pursue a Master’s degree in Social Work at Widener University where I am studying today. I’m also currently a program manager at Mental Health Partnerships. I work with chronically homeless men and women, many of whom have experienced trauma, substance use disorder, and other mental health challenges. It’s the most rewarding work that I have ever done in my life, and I absolutely love it. I’m passionate about helping others improve their lives because so many took the time to help me when I was in a bad place. I wanted to pay that forward and help individuals change the trajectory of their life regardless of what they’re going through.

I think a lot of people have the idea that recovery is a process that doesn’t have any relapses. I think we need to consider that the relapse is a part of recovery, and we don’t always get it right the first time. Don’t give up on your family member just because they experienced a relapse; a lot can be learned from experiencing a relapse. If you look at my story and you consider the first time I got out of jail, I relapsed right off the bat. When I went back to jail again, I was forced to consider what went wrong the first time. The pathway to recovery is different for different individuals. When you think about interventions, I was able to initiate and sustain recovery through the pathway of actually being incarcerated. I considered going to jail as something that actually saved my life. However, when you consider my brother, he went to jail with a crack cocaine addiction and came back out of jail with an opiate addiction.

It’s inaccurate to believe that incarceration will cause all people to reevaluate their life choices. It might work for some but not for all. We can’t take a cookie cutter approach to recovery. We need to understand that some people will respond better to medication assisted recovery, some will work better with complete abstinence recovery, some will improve with faith-based treatment, and others will succeed with harm reduction strategies while tapering their use. We shouldn’t shame anybody for the methods of recovery that work for them. On top of having the loving support of my wife and family, it was incredibly helpful to connect with others battling substance use disorder. Seeing others who shared my background getting better made it evident that recovery was in my power. It’s a risk to invest in education as an education doesn’t automatically equal a job, but when you see people taking the risk and reaping the reward, it inspires you to keep moving.

This is why I am sharing my story, so that somebody who’s early on in their recovery or active addiction can look at me and realize that if I can do it, they can do it. There’s a resilience to the human spirit that shouldn’t be discounted. I’m thriving in recovery. I’m a first time homeowner and am able to provide for my children with a rewarding job. A few months ago, I found myself sitting next to the Governor of Pennsylvania, the Mayor, and the Chief of police. This is something I never would have dreamed would happen while I was in prison and going through withdrawal.

We need to stop seeing people as addicts that will never change, but as individuals who have potential for great things.