"So, I just held him. I said, "We probably could have beat this but we just ran out of clock,” because that’s what I always used to say whenever we lost a football or lacrosse game."

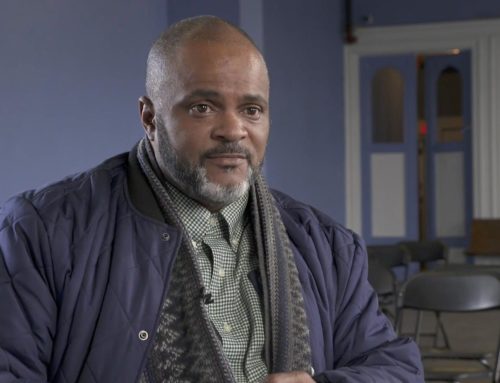

I grew up in Ohio. I have a background in music and I worked in various industries doing physical labor. I’m married to a beautiful woman. I usually give thanks every day of my life for her since she’s one of the best things that has ever happened to me. I have three children, two daughters, my son who is with the angels and spirits now, as well as a son-in-law and a beautiful grandson who is 17 months old and getting into everything. My oldest daughter is 30, my younger daughter is 26, and Derek was 20 when he passed from an overdose.

Derek was energetic. He was kind. He was funny. He was creative. A lot of people share their Derek stories with me. People have come up to me in restaurants or wherever and explain how he changed their lives or how he stood up for them when they were being bullied. Always in those conversations the word “kind” comes up. He was kind.

Derek played every sport and excelled at all of them. He loved lacrosse, he was a tough player, and always came up with the ball. His primary sports were lacrosse and football. I have a lot of fond memories going to practices and games together.

We also spent a lot of time outdoors hunting and fishing. When Derek was little, we would go into the woods to read Doctor Seuss books and cut up apples. We would always talk about Mother Nature. I remember one day, it was pouring down rain. He couldn’t even talk yet and he put his boots by the door and just looked up at me like, “Let’s go outside.” I said, “You know it’s pouring down rain,” and he just looked at me, so we went outside to play in the rain.

We did everything together when Derek was growing up. He was like my shadow. Then, when Derek was in eighth grade, I noticed a change. He had a different group of friends, even though up until that point, he pretty much ran with the same group of friends. I had asked him why he was hanging out with this new group, and he was vague about it. I didn’t recognize the red flag at that point, but that probably was the first indication he was using drugs and alcohol.

Looking back on it now, there were other red flags. Sometimes I smelled weed on his clothes, and when I confronted him about that saying, “This is not okay.” He said, “Well, everyone’s doing it.” I responded, “Not everyone.” We had more similar conversations throughout middle school. Older kids would pick him up, he would bolt out the door, and go drinking with them. He had his first experience with heroin in high school, when he was probably under the influence from alcohol and marijuana.

When I found out how badly his drugging and drinking got, I thought to myself, “Oh my god, no. I’m the Dad. I should be able to do something, talk to him, and be able to stop this somehow.” Earlier on, it was tough to realize that I wasn’t as powerful as addiction, that it was bigger than me. I started seeing a serious downturn when Derek was 16 years old. I found him unresponsive twice. The first time wasn’t as bad and I was able to wake him up. The next time, he wasn’t breathing too well. That’s when I made the decision that I’m not just going to bury my head in the sand. I’m going to do something. The friend group he was running with continued to go to high school here, and I thought it wasn’t going to end well if Derek stayed in this environment. We had a family meeting and decided on a course of action. We sent Derek out West to connect him with treatment and healthcare professionals to get healthy and finish out high school.

We sent him to a wilderness program in Utah. He hiked daily, read books, participated in group and one-on-one therapy, sewed leather bags, whittled wooden utensils, and got a complete break from his current lifestyle. He loved it. He was an outdoor kid. After three months, he graduated from that program and was ready to finish high school. Derek said, “Part of me wants to stay here out in the wilderness.” He needed to finish high school, so we made the decision as a family for him to join an all-boys school on a 300-acre horse ranch in Arizona. He loved equine therapy, accelerated at school graduating with a 3.9 GPA, and participated in frequent group and one-on-one counseling, and the boys generally loved each other. I would see them pass each other on the campus and hug each other.

He could have actually graduated from the ranch sooner, but they had levels that you had to attain, and he stalled at times. He didn’t have the willingness at some points, but he did graduate from there with honors. He transitioned to an assisted living program with a few other boys from the ranch who he made strong friendships with. He started college at University of Arizona and got a job. Things were looking good. I was hopeful at some point that he would be able to come back home, but a greater part of me knew that it probably wasn’t the best for him to come back here where people, places, and things might reconnect him with some not-so-healthy friendships. Ultimately, he did end up coming back home.

He did seem like he had latched onto recovery and he did have what I thought was a good foothold. He had a sponsor, he worked a program, and was going to meetings. He would tell me, “I’m doing what I need to do,” and I felt pretty good about that. Ultimately, he wanted to test the waters and take some college classes in Philadelphia. I was hesitant about that, but that’s what ended up happening. So, I told him, “We’re giving this six months. If you go down to the city and I don’t know what’s happening, I’m going to pull the plug on everything – the apartment, school, I’ll cut everything off. The expectation is that you’ll be sober. If I find out you’re not, then my financial support will be gone.”

Right before the end of those six months, a very good friend of his called me and told me that he was using. I believed that it was solid information and confronted him. There was denial. When I continued to press the issue, there was minimization. Then, I said, “We need to be honest with ourselves.”

When we pulled out financial support of his apartment, he said, “I can’t believe you’re going to turn your back on your only son.” That really hurt and was hard for me. I thought of things I could have said, but I didn’t reply. I don’t think many people realize that when someone suffers from addiction, the addiction controls them. The disease is bigger than what they want to do. It’s not the case where people can “just say no.” After we parted ways downtown, I really wasn’t sure what was going to happen. He didn’t move home. He couch-surfed for a while, and according to him was homeless for a little bit when people didn’t take him in.

It made me feel awful to be honest with you. But, I have some friends who had been in the same position, and they flat out told me, “If you let him in, addiction wins,” and that was something simple that stuck with me. At the same time, part of me wanted to have him come back home because I’m still his Dad. I wanted to “fix” it even though I knew I couldn’t and that’s part of my disease of codependency and enabling. I didn’t want to do that and ultimately knew that it wouldn’t help. Throughout that time, we had some conversations when I told him, “All you have to do is tell me you’re done. Just say something along those lines, and I’ll be in 110%. Financially, physically, emotionally, spiritually, I’m there 110%. You just call my phone. It’s on 24/7.” And there were a couple of nights when he called me up and said, “Well, I’m almost done,” and I said, “That’s not really done. Are you done?” I think he got close, but he just couldn’t say the words.

When Derek was living in Philadelphia, I called him one day to tell him that I’d be downtown to see one of my doctors, so maybe we could meet up for lunch. He said, “Well, I’m working today,” and I said, “Okay. I’ll stop by your work.” I stopped by the restaurant where he was working, and we had a quick sandwich together. I was going to drive home after that but I really wanted to talk to him about him using. I had about five hours to kill before he got off work. I didn’t know I was going to wait that whole time. I just walked around the city. I ate a little more, prayed, and asked God for guidance. I thought, “What am I going to tell him?” I called one of my friends and said, “I don’t know what I can say. I’m just not that powerful, but you know maybe I can pray for God’s will and guidance to say something that will get through to Derek.” My friend said, “You may want to prepare yourself because this could be one of the last times you ever get to talk to him.” I sat with that feeling. It was awful.

I waited and showed up when he got off work, and he was shocked that I waited that whole time. He said, “I never expected you to stay downtown this whole time. You waited all that time?” He knows I don’t like being in cities. I was driving him back to his apartment, because at that time he had his own place, and I said, “I have something I need to tell you, and it may be hard to hear, but can you be honest with me? I feel like we need to be honest with each other.” He’s said, “Yeah, okay Dad,” and I said, “I don’t know where you’re headed with this. I don’t understand. Maybe you could help me out and explain to me where your thinking is. Do you have a plan?” At that point, he had already been revived with Narcan once that I know of, and that’s why I pulled over to the side of the curb and said, “A regular person doesn’t get Narcan. What’s happening?” He couldn’t say anything. He actually cried a little bit, which was hard for him as well. Then, he just sat there for about five minutes and never said anything. I said, “Well, okay. Do you want to get something to eat? We can spend some time together.” He said, “No, just drop me off at my apartment.”

I respected his wishes, and then I drove home. It was a long drive because when someone is in the middle of their addiction, you don’t know when you may get that phone call. Through all of this, I made a decision that I wanted to have some good times with him, and we continued to be part of each other’s lives. For instance, we saw the 76ers play the Cavaliers, which was special to us since we’ve always been Cavs fans, and we saw the Eagles win the NFC championship game against the Vikings, sitting in the second row behind the players’ bench on the 45-yard line.

Eventually, Derek moved up to Doylestown. He was working in landscaping, and the guy who he was working for said, “He’s the hardest worker I’ve ever had.” Just to share a quick story, his mom bought him plastic tools when he was about four-years-old. I told her, “He’s not going to want that.” He held it up, looked at it, and he dropped it on the floor. So, I got him real tools. They were steel and hickory but were small, and he loved using them. Anyway, he was back in Doylestown and working. He was living in a motel just until we could find him an apartment, since he looked at a few places that wouldn’t accept him. We took his car when he first started using again, so I was driving him to and from work each day. He usually seemed to be in a good mood, but I still don’t think he really surrendered—and I know today that someone with the disease of addiction needs to surrender. It’s an inside job. There’s not enough love or money that can make someone get sober. They need to want to do it for themselves.

One morning, I picked him up for work. Apparently, they needed more labor that day, so he contacted one of his old using buddies. I said, “I’m going to tell you just one time, some people do not mix. I don’t know why you’re hanging around this guy, but it’s not healthy in my opinion.” A few days later, I went to pick him up for work. I called him because many times I would get him breakfast on the way to work. He didn’t answer, and I got a bad feeling. When I got there, that same young man came flying out of the room and said, “Oh my God, Mr. Wankum, I think Derek is dead.” I ran to the room as fast as I could and started CPR on him. I’m trained in CPR and Narcan, but I didn’t have any Narcan with me. I had it at my house. He already felt cold at that time. I was trying as much as I could. It seemed like it took forever, but it was probably only five or ten minutes before the EMS people got there. They said, “You have to leave the room,” and so I did. I just went back to the car and sat down because I felt like I couldn’t stand up.

Then, they told me I could go back in and asked me if I was ready for the result. I went up and I held him. He was even colder than before. The EMS people told me, “It wouldn’t matter what you did. You’re about three hours too late.” So, I just held him. I said, “We probably could have beat this but we just ran out of clock,” because that’s what I always used to say whenever we lost a football or lacrosse game. We just ran out of time. And that was it. It’s crazy because he called his mom the night before and said, “Dad’s always been there for me.” I didn’t hear it, but according to my wife he went on for over 20 minutes, which is a long time for a young man who was very short on the phone.

Losing my son, my youngest child, my only son, feels like I was robbed. I know my truth today is that I can either isolate or I can try to be solution-based. For me, I always try be solution-based. How can I be of maximum service to others? I do lot of service work—and it’s not about me. Honestly, when I give, I receive almost unequivocally. For me, part of the healing process is to give.

I also work through my grief by starting each day with prayers, readings, and meditation and incorporate Native American spirituality. I don’t stray from that practice because when those three things come together, I set my intentions for the day. That helps me to get my head screwed on right so that I can carry on through the day. I’m not going to lie, it’s hard. Sometimes I’ve been walking in the yard or in the kitchen when it all just piles up, and I hit the floor like I’ve been shot. I read something from a guy who lost a loved one, and he talked about someone who broke her ankle and then asked the doctor on a follow-up visit, “Why is my balance bad?” This writer said that many times this same thing happens after the loss of a loved one. Our life is out of balance. I have to remember to be gentle with myself as I continue to get my spiritual groove on every morning. That’s what really helps me to help others, and helping others is what drives me today.

Today I do work with teenagers. I speak in treatment centers and rehabilitation facilities and lead family support groups. As I mentioned earlier, my phone is on 24/7, a few feet from my head. I’ve mentioned this to many young people and people at my son’s service. They know that I’m safe and they can call 24/7. I do field the calls, 3:00, 4:00, 5:00 in the morning and I’ll suit up and show up. If I need to drive somewhere, I will. No matter what, I’ll talk with somebody and say, “Yeah, I’m here,” and “Whatever you’re doing or going through, there’s a better way.” The teens I work with will come up and hug me many times when they see me. And after we meet for a while, they’ll hug me before I leave. For me, that’s priceless. I don’t ask any questions about what’s going on in their family, but who knows if they even hug their own parents. To me, that’s a beautiful thing. Helping anyone makes me feel like I’m making a difference, like I’m being part of the solution.

My advice to others who have lost a child, or who have a loved one struggling with addiction, is to find a group of people who understands and gets it, because you’re not alone, and if you feel like you’re alone, that’s not a good place to be. Someone once told me, “Don’t go inside your own head by yourself. It’s dangerous.” As funny as that sounds, today I know I can pick up the phone and call people who are healthy, and we can talk. When I was younger, I thought I’d just do everything by myself, but today I know that I can reach out and talk to people who have lost children, and they understand as no one else can.

Grief is not one size fits all. For me, I have a hard time crying. There are many different paths and journeys that grief takes for people. I mostly just remember the good times. I choose, and I do have choice, to remember the good times. There were so many good times. Most of them when Derek was younger, obviously before he started using, but I cherish all the time we spent together.

This is why I am sharing my story. I want to get the message out because I know so many people who have died. I can’t think of anybody who doesn’t know someone who’s tangled up with drugs, alcohol, heroin, or who’s died. Meanwhile, the car is shining, the lawn looks beautiful, every little thing looks nice, but nobody wants to talk about the elephant in the room. Someone needs to have a conversation to get it out there. We can always do something to be part of the solution.