"At age 27, I had a great job as a social worker in Philadelphia and I fell down some steps at my job. I needed to have surgery for a torn meniscus. That work-related injury would change my life forever."

I was born in Detroit and grew up in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. I grew up in a strict, Christian household. My dad was a minister and later became a pastor. My mother was strict and used to say, “a women’s work is never done,” so I had a lot of household responsibilities like cooking and cleaning at a very young age. I’m glad now that I have these skills as an adult. In high school, I was very unpopular. I was the awkward, skinny girl with thick glasses that everyone made fun of. I loved all the boys on the basketball teams and the football teams, but they never gave me the time of day. So, I grew up kind of awkward, and I had friends, but grew up always having my own mind. I made my own choices and was never affected by other people and what they did.

I was close with my siblings growing up. Two of my siblings are from my biological father, and then I have three siblings who have a different father. My mom married my youngest brother’s father, George, 35 years ago, and he’s the person I acknowledge as my dad since he’s been in my life constantly. We used to be crazy, funny kids. We used to jump out of apple trees. We used to steal people’s bikes and run around people’s yards. We were crazy. People wonder how I’m so tough now, but my brother, Malik, and I used to wrestle and watch WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) on Saturdays. I was split between “a woman’s work is never done,” put on an apron and bake, while also jumping out of apple trees and acting like Superman and all the wrestlers from the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Whenever I speak motivationally and meet different people, I tell them that I had never abused drugs my whole life until my addiction. All my friends were drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana, trying different things, and I was always the leader, the mom out of the bunch. I would be the one saying, “No, listen, I have to drive,” or, “We have to leave right now. You’re not leaving with this guy, let’s go.” So, I was that woman who kept everybody together in the clique.

At age 27, I had a great job as a social worker in Philadelphia and I fell down some steps at my job. I needed to have surgery for a torn meniscus. That work-related injury would change my life forever. I was prescribed Lorcet, which is hydrocodone and acetaminophen, one every four to six hours, and that is what I took. Then, at some point, I noticed that I felt different and I liked how I felt. I felt powerful, so I said, “You know what? Let me take two more. Let me just see if I can heighten the feeling.” And that is how my addiction was born.

I realized I had a problem because I was trying to maintain both doctors prescribing that medication so that I could have extra. I didn’t know it was a problem at that point. I didn’t realize that the more I had, the more desire I had to take more. I still didn’t know it was an addiction; I just started taking more. Now being a certified Family Recovery Specialist, I can look back and say, “Okay. You weren’t educated about your previous situation, and that is why you loved the hydrocodone.” I didn’t know anything about the medication or risks. I was addicted to opioids for 10 years, but it took me about three years to realize that I was addicted. My mind was dead, and I just cared about doctor shopping and going to pharmacies and getting prescriptions. I did not think about anything else.

There were periods of time when I ran out of Lorcet and I didn’t have a doctor’s appointment, so I would try to request for an early refill. If I couldn’t get the medication, I went through withdraw and it was brutal. I was waking up in the morning sick, unfunctional, and sweating. When you’re taking opioids, they suppress everything in your body. They suppress your sneezing, your yawning, your breathing – everything. So, when I didn’t have them, I’m yawning, I’m sneezing, and I’m in the bathroom sick all morning. That’s when I knew it was a problem.

I have a website and a blog called Chase No More, and one of my posts is called “You Do the Math,” where I added up the number of pills that I was taking on a given day during my active use. I took the amount of hydrocodone, which is 10 milligrams, and the 650 milligrams of acetaminophen, and I added both up. At the height of my addiction, I was taking take 30 pills a day. I would wake up, eat a bowl of oatmeal, and take six or seven hydrocodone. I would go about my day, and then four or five hours later, I would eat lunch and take six more hydrocodone. I thought I was doing great in my life, but in reality, I was 97 pounds and my goal was always to get more opioids. If I went in a pharmacy and they flagged me and said they couldn’t fill the prescription, I would say okay and walk out. I would then go through withdrawal for a certain period before I would go to one of my other doctors and get another refill. I was on a rampage. That is how my life was.

If I lost a doctor, I would get two or three more. I’d walk in with a knee brace on and say, “Hi, I had a meniscus repair procedure done and my doctor’s out of town. Are you taking new patients at this time? And do you take cash co–payments because I live in New Jersey and I can’t use my insurance here?” So, they would say, “Oh, okay. Yes, we take new patients. Do you have your charts?” I would take notes from other doctors that were writing me prescriptions, and sometimes I would change the dates on the charts to make it look like it’s been a month since they’ve prescribed it. I would take that into the new doctor’s office, they would examine me, and then write me a new prescription and say, “Okay, we’ll see you in four weeks.” That is how I gained all of my doctors. Doctors are trained now to look out for signs of misuse like early refills, body language, or symptoms of withdrawal. Somehow, I learned the system and managed to slip through the cracks.

My addiction started affecting my life a lot. My life was really out of control. I started doing crazy things, especially with eating. I went through a period of time where I was obsessed with certain foods. I was eating water ice so much. I mean, I would think, “Okay, it’s October. They’re closed for the winter. I’m going to find a location in a mall that’s open all year round, and I’m going to go get my water ice.” So, I would travel from Delaware all the way to New Jersey to a mall that had this water ice store. I have a picture on my social media with gallons of water ice. I didn’t have anything in my freezer except water ice, gallons of it. These obsessive-compulsive behaviors were related to the addiction. I was eating crazy, I was sleeping crazy, I wasn’t breathing out my nose, and I started to have a lot of health problems from the opioids.

My professional life was also going downhill, although no one at work ever knew I was using pills. I was so functional in a lot of ways. Back then it wasn’t an epidemic and people weren’t looking for certain signs. I had a high profile job, and I had cases working with high-risk youth all throughout New Jersey. I had clients at group homes and minimum prison facilities for kids that are high risk for different crimes. I’m a tough, inner-city girl, so they put me with some of the toughest cases. I would show up wherever they sent me, including the projects in Trenton. I’m just fearless. Taking opioids was how I felt I could cope working with these kids in high-risk lifestyles. But my addiction was affecting my life because I would drive to clients and stop at a rest stops and accidentally fall asleep. Or sometimes I would intentionally just get off the highway, find a neighborhood that was safe, lay in my car in the backseat, and sleep.

I have a crazy story in my upcoming e-book titled, Addicted in Silence. I have a story about one of my clients. She was 17 years old and pregnant. I was her social worker, so I was taking her to prenatal appointments, Lamaze classes, and being with her 24 hours a day for whatever she needed. When she went into labor, I was going through withdrawal. I had a doctor’s appointment later that day to get more pills, but while in the delivery room, her foster mom and I had to hold her legs for her to push the baby out. I was sweating and nauseous, and I was like, “Listen, I have to use the restroom.” They were like, “What are you doing?” I said, “I feel sick.” She was vomiting in a bed pan, and I was in the bathroom vomiting from withdrawal. This was my job, and I couldn’t do it.

There were also lots of situations when I was driving and knocking off my rearview mirrors or getting into dangerous situations because I was nodding behind the wheel. There was one time when I was driving from Claymont, Delaware, (because I was living there at the time) to Willingboro to see my mom. I just remember waking up on the opposite side of the road. I had crossed the median. That’s the thing about the opioids. When you’re taking a high dose, you can nod out or blackout at any time. Miraculously, no one was hurt and there weren’t any police around. So, I backed my truck up out of the grass, got back on the highway, and drove. One time I was driving into Philadelphia and woke up at 2:00 AM on the opposite side of the Tacony–Palmyra Bridge! I woke up, and I had knocked all the dividers down in the middle. I was on the other side, but there were no cars. That’s why I know I’m meant to be here and meant to share my story for people and give them hope, because I was at rock bottom

My addiction affected my personal relationships as well. I was withdrawn. I didn’t want to be around people. Everything that I wanted to do was based around opioids. I never traveled. I had never been out of the country. I went to LA for the first time yesterday. I forgot how it felt to fly, but that’s because my life was so consumed with the opioids.

I went through periods of time when I was basically homeless. I don’t want to say homeless because I could’ve gone home – but I felt homeless because I wanted to be in certain places that feel comfortable. My girlfriend, Y, lived in Philly, so I stayed with her a lot of times. She had two kids at the time. I just remember days when I was cooking breakfast for her kids and was going through severe withdrawal or helping her kids with their homework while trying to get to a doctor’s appointment. Everything was crazy, but Y didn’t understand what I was going through. She did not have an inkling of a clue.

As far as my parents, my dad didn’t have a clue and my mom knew something was going on but couldn’t put her finger on it. My dad passed away two years ago. He had become a Pastor and I’m happy to say that I was clean for seven years before he passed away. I know he’s smiling down on me.

What’s really crazy for me is that I spent the height of my addiction in and near Abington on PA 611, which is right where this Sharing Your Story Initiative is headquartered. I’m going to tell you a little story about my addiction when I was in this area. I was going to all the different pharmacies and supermarket pharmacies in the area. The day I got clean, it was up here at a supermarket parking lot. That was when I had my first “aha moment.”

I experienced many adverse health consequences of my use. I was looking at the pill bottles every day, but I never read the warnings. I know that taking too much of this medication could cause serious breathing problems, so I thought that meant chest pains or something like that. For me, the opioids actually shut off my nasal passages. I would have to sit up sleeping because I couldn’t breathe. It was so bad. I started taking a certain type of nasal spray which was very expensive, and I was coughing up phlegm that was green from my nasal passages. I don’t know if I had an infection, but I was always taking antibiotics for my nasal passages.

I started going deaf. At first, I just thought I had an ear infection. Going deaf is a crazy experience. I lost my hearing in an eight-month period of time. And the crazy part is, I don’t even know how long I was going deaf before I could not hear, because there’s a period of time where you just have symptoms that lead up to the hearing loss. I experienced ringing and muffling. I did not know what was happening. I was telling people, “Okay. Talk on my right side,” so people would be like, “Okay, so what is going on?” I’m like, “I don’t know. My ears are messed up. Talk on my right side.” I went to an audiologist who gave me a hearing test. I started going through those hearing tests every other month. It was a dark moment for me because I was losing my hearing and I didn’t know it.

The audiologist said to me, “You are rapidly going deaf. You’re suffering from profound hearing loss.” First, they called it sudden sensorineural hearing loss. But at some point, the hearing was just getting worse, so he said, “We’re going to fit you for hearing aids. At first, I went through severe depression about that because I felt like an old lady. But then, I got to a point of desperation where I wanted to hear, so I didn’t care about the old lady part.

Eventually, at some point, I had another “aha moment.” I was sleeping on my couch in Delaware – and was still popping 30 pills a day throughout the whole process of the hearing loss – when I woke up and it was silent. I couldn‘t hear anything, so I thought, “Where’s everybody at? It’s quiet.” I changed my batteries on my hearing aids and I still couldn’t hear anything. It was silent. I could hear but it was like shadows, like if you were a blind person and you really couldn’t see the person but only the shadow. I thought, “Oh my god. This is crazy.” I went outside to my truck and started beeping my horn. I couldn’t hear that. I came back in the house, I opened up my silverware drawer, and started rattling knives and spoons and forks. I couldn’t hear that. It was like a muffled sound. At that point, I texted my mom and said, “Mom, I can’t hear no more! I don’t know what’s happening. I can’t hear!” She’s like, “You have to make an appointment to go back to the audiologist.” And on that day, I realized that I was deaf.

Also talking about the physical impacts of opioid addiction, I lost my libido for six months. I also went through a period of time when my vision looked blurry. My eyes were cloudy. So, when I got clean off the opioids for maybe two or three weeks, I got up, I looked outside my window, and I was blinking my eyes. Everything looked so clear, so maybe these opioids suppressed my vision too.

My process of recovery was different. I always tell people there are many pathways to recovery. My pathway was going cold turkey. No one should ever do that because you can overdose or die, especially if you go through a period of withdrawal and then you go back to the drug. But for me, that’s how I got clean. It’s funny to me now, because I have people reaching out to me internationally and they are like, “I need help. What type of advice can you offer me?” I always tell people to seek a doctor for medical advice. I tell people, “You can lose everything and still want the drug.“ You can lose your kids, your mom, your job, your house, your car, you still want the drug. I experienced some of that, so I know.”

I started being flagged in every state because my name kept coming up in every pharmacy system, so I had to figure this out. What am I going to do now? How am I going to keep supporting my habit? This has gotten out of hand.” And I was saying to myself in my head, “I’m not buying no drugs off the streets. I’m not going that route.”

In 2010, I got the nerve to go into a detox program in Freehold, New Jersey. I guess I had an inner battery that sent a shock, like an inner defibrillator warning me, “Hey, do you want to live or die?” But I followed that inner defibrillator, and I said, “Hey Kay, I want to live.” I had Medicaid insurance at the time. I called a friend up. I said, “Hey Bob, please, I’m really going through a lot. I’m sick. I’m fighting for my life. Can you take me to this detox?” He was like, “Okay. Yes, Kay, I’ll be happy to.” He drove me all the way there. I was in the back seat laying down, listening to my iPod barely hearing anything. I was going through withdrawal and was feeling everything – sweating and burning up one minute and the next minute I would be freezing under a blanket.

Once I got to the detox, the people running the facility said, “What is your drug of choice?” I told them, “Lorcet.” They said, “Lorcet? What is that?” I told them that it’s hydrocodone. They did not know what it was. This was in 2009 or 2010, and they had no clue of what hydrocodone, Lorcet, narcos, or Vicodin was. So, I felt defeated right away, because I felt like if they didn’t even understand what my drug of choice was, how would they be able to help me?

The detox was one of the most awful experiences I ever had. I had packed the nasal spray I mentioned and Zantac that I was taking every day because I was having severe digestive problems from the opioids too. The people managing the detox had to take all of my medication away. They said, “We have to supervise what we give you.” So, I had hell in that place. I couldn’t breathe, I was spending all my time in the bathroom, on the toilet or in the bathtub trying to comfort myself with restless leg and arm syndrome. My blood pressure dropped with all the body fluids being lost. So, I told them I need to go to the hospital. I felt like I was going to pass out, so they called 911 and had an ambulance transport me to the ER. They had me on a stretcher in the hallway the whole time. They treated me like I was nothing. I felt like they thought, “Okay, we got a junkie in the hallway. Just let her sit there, we can’t give her nothing for withdrawal.” That’s how I was treated. After I left the ER and they put me back in the ambulance and transported me back to the detox center, I called my friend Bob. I said, “Come get me. I’m out of here.”

Bob came and got me, and I went back to my opioids. I finally mustered up the courage and got clean in 2010, a year later, cold turkey. But I’m going to tell you why, because I said to myself: “I’m not going back into a detox. I’m not dealing with that awful experience again. I would rather be on my couch detoxing than to be in a place around all these people who didn’t understand what I was going through, what drug I was taking.” I cold turkey-ed on my couch. My mom and dad came down. When I left that supermarket parking lot here in Willow Grove on PA-611, I was like, “Mom, I can’t do this anymore.” I told her, “I’m very sick.” I’m texting her. It’s four in the morning.

I told my mom that I was sleeping in my car. A cop knocked on my window asking me if I was okay. I told my mom that I was going to try to drive all the way home to their house even though I was going through withdrawal, but my mom said that she and my dad would come to me. My dad being a Pastor came with his Bible. My dad said, “We’re going to get you through this, baby doll,” and that was it for me. I never took another pill. I just pulled myself up by my bootstraps and said, “Okay, Kay, you have only have two choices: life or death.“

Recovery is amazing. Like Luther Vandross says, “It’s so amazing to be loved!” There are so many layers to recovery. It’s like baking a layered cake. First, you go through the physical withdrawals. That is hell. I was sick for months. I couldn’t keep nothing down. My mom made me a big pot of northern beans and white rice and said, “You have to eat.“ I was like, “Mom, I can’t. I can’t. I don’t want no rice.” So, my mom started buying me Gatorade G3. She said, “Keep drinking, keep drinking, you have to stay hydrated.” And we all know that moms know best! My dad was right there with me too. He prayed with me. He said, “Baby doll, the first thing you have to do is forgive yourself.” I agreed with him. I felt so guilty. He said, “Most of your healing will come from forgiving yourself.”

The physical part of recovery is about trying to get back to your normal body. I’m talking for me being able to walk up and down the steps. I had restless leg and restless arm syndrome severely. I had to sit in a hot tub for hours to calm my limbs. I was running up and down the steps for two days. My limbs just wouldn’t stop moving.

The second part I experienced after going through the physical part was severe paranoia and being extremely emotional. I thought the cops were looking for me because my name was popping up on pharmacy databases statewide. It wasn’t a prescription drug ring; it was ALL ME! I went through severe paranoia and, also, I was fully deaf and was still trying to cope with that.

I went through some periods of extreme happiness and appreciation too. I would often cry from happiness because I felt like, “I’m getting through this! This is crazy! I’m getting my life back!” Even though I was still deaf, I would get in my car, roll the windows down or put the top down and blast my music. I love music and used to be a deejay. After these emotional phases, then I went through the real life stuff – adjusting to living life without no pills.

I learned the gift of transparency and I developed so much passion to help people who were fighting the fight of addiction as I was. I understand that what I didn’t have years ago is the information that I’m giving out right now. I was a regular person just like anybody else. The most amazing feeling in the world is to help people get through recovery and to have people reaching out to you for help. It’s amazing to realize that you are helping people by sharing your story. I call myself a hope dealer, and I understand that I have a calling on my life to help others.

When in the early healing process, I cried a lot. Eventually I began to get stronger about telling my story. I went to church, I read a lot of books, and I started speaking out about my experiences with opioid addiction. I was desperate to get my voice heard for years. Now people know who I am and will walk up to me and say, “Hey, I’m following you on social media,” or that they saw me in the newspaper. Recovery is the best thing I ever experienced in my life. My life was suppressed for a decade. I was living in a glass house, and kicking on the doors saying, “Somebody help me! Somebody help me!” But nobody could hear me, and now I’m being heard.

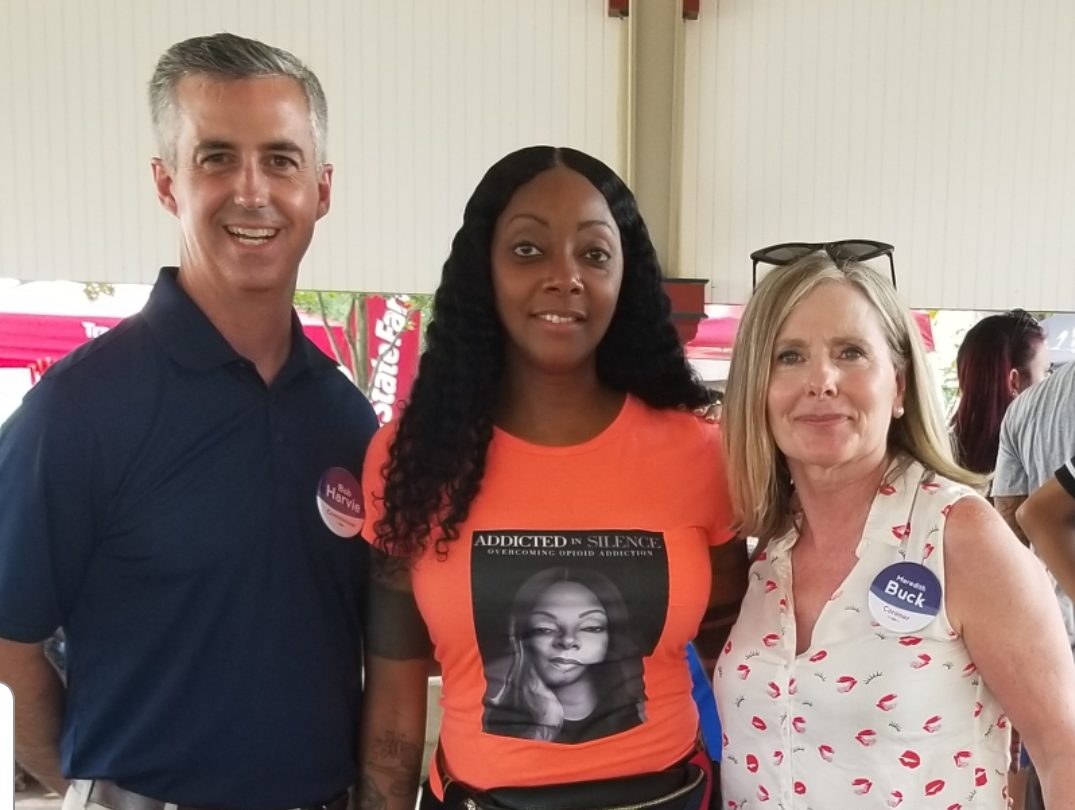

My friend Buffy pushed me to grow my social presence. She’s a friend I grew up with and she’s amazing. I love her. One day, she reached out to me on social media before my dad died, and she said, “Okay. You keep saying you’re a public figure. How many friends do you have on you Facebook?” I said, “About 300 friend requests that I haven’t even accepted yet. I don’t want people in my business. I’m not talking to these people.” She said, “Kay. You’re ridiculous. I’m done with this. Every day we’re going to add 100 people to your Facebook.” We maxed out my Chekesha K Ellis Facebook page with 5,000 people and other social media platforms with over 5,000 friends. I started doing live videos, taking selfies, making my presence and my name heard. She helped me build up my social media presence. Now I have t-shirts, sweatshirts, coffee mugs, cell phone cases, socks and a lot of different items to represent my brand! I have an entire movement now!

My organization is chasenomore.org, which provides assistance for individuals statewide and nationwide who are struggling with substance use disorder. I provide resources and support in communities statewide. I also educate communities on the life–saving drug, Narcan, a drug that is saving lives all over the world from opioid overdoses. I have successfully placed people in treatment centers.

People really have a different tune when they’re directly affected. People can be judgmental and look at you and they say, “That’s a choice.” It involves some choice, but addiction is a disease, period, and you just cannot look at people and write them off. I tell people all the time, “You can love them from a distance, but let them know that you’re not giving up on them, and that there’s hope for them.”

This is why I am sharing my story. It’s amazing to wake up in the mornings, have some turkey bacon, some eggs, and a cup of tea, and sit on my porch and not have to run to a doctor or turn down invitations because in my mind I’m saying, “I’m not going to have enough pills to get through that.” I was walking around everyday people and I was addicted in silence. Nobody knew, so I’m going to be the voice for people, so they can say, “I need help. Can you help me?”